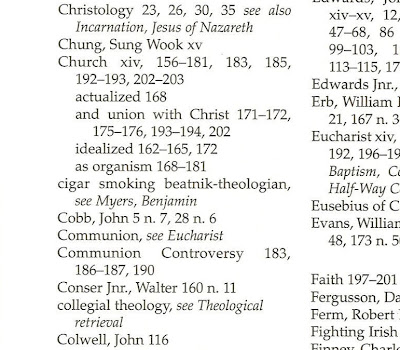

Today I received my copy of Oliver Crisp's latest, Retrieving Doctrine: Essays in Reformed Theology (IVP 2011). For an extremely important piece of analytic theology, I refer you to the index:

And again:

It's good to see that I have established a reputation for excellence in my field...

Anyways, I also wrote a blurb for the back cover: "Oliver Crisp argues here for the ongoing vitality of several diverse Reformed traditions. He is drawn to the curious, untidy edges of the Reformed tradition, to unexplored (or forgotten) tensions and problems which the tradition has produced. In the midst of these tensions, Crisp finds new possibilities for contemporary theology." Kevin Hector also blurbs it as "an eminently clear, insightful book." So put that in your pipe and smoke it.

Monday, May 16, 2011

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

Off the Shelf: three more types of reading

As a sequel to six types of reading, here are another three types. I had also planned to mention Secret Reading, Stolen Reading, Restless Reading, Abortive Reading, Fetishistic Reading, and Travel Reading – but I got frightfully distracted by all the little pressed flowers inside the pages of Dr Johnson. So I might discuss a few more types of reading next time.

Books mentioned in this video:

Books mentioned in this video:

- Samuel Johnson, Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets [1779]

- Anne Hunt, The Trinity: Insights from the Mystics (Liturgical Press 2010)

- Edward Morgan, Incarnation of the Word: The Theology of Language of Augustine of Hippo (T&T Clark 2010)

- Khaled Abou El Fadl, The Search for Beauty in Islam: A Conference of the Books (Rowman & Littlefield 2006)

Once more with Rowan and Lulu

Oh, and speaking of children: my recent post on Rowan Williams' letter to six-year-old Lulu was the most popular post I've ever had at F&T. It was shared over 4,000 times on Facebook, and received loads of extra visitors from StumbleUpon. All in all, the post got about 27,000 hits in the first three days – and it's still making its way around Facebook.

I found this very intriguing: I wonder why Rowan's letter struck such a chord with so many people?

I found this very intriguing: I wonder why Rowan's letter struck such a chord with so many people?

Labels:

blogging,

children's theology,

Rowan Williams

Sunday, May 8, 2011

Giggly theology: Owen responds to Off the Shelf

My video on six types of reading has provoked a brilliant and provocative response from one of America's youngest philosophers. Here is Owen, son of R. O. Flyer and grandson of Roger Flyer, subjecting my video to a stringent critical analysis:

I'm especially impressed by the way he bursts into peals of laughter when he hears the name "Chesterton": the word tends to have the same effect on me.

In fact, I once missed out on an important job opportunity simply because the interviewer – the dean of Harvard Divinity School – happened to mention the name of G. K. Chesterton. We sat in the autumnal light of the dean's office, facing one another across a polished mahogany desk beneath the shadow of towering bookshelves and the high baroque majesty of that Ivy League ceiling. "... And that's the real problem with someone like G. K. Chesterton," he said.

I cleared my throat. I shifted in my seat. I felt my nose twitch as I stifled a little giggle. I concentrated all my mental powers on suppressing the shaking that had started somewhere deep in my diaphragm. I wiped a solitary tear from my eye. I breathed.

At last after a few moments I had calmed myself. I coughed politely into my hand, and opened my mouth to make an erudite remark about Catholic thought on distributist economics – when, to my horror, the dean leaned back in his chair, coffee cup in hand, and said the dreadful word again: "Chesterton." All my defences collapsed. It was as though a gigantic hand had seized me by the rib cage and given me a fierce shake. I covered my mouth. I heard a terrific snort. I wiped my eyes and said, "I'm terribly sorry, I do beg your pardon. We were speaking, I believe, of Ches – Ches – Chester –"

And then it happened. The Dean of the Divinity School leapt from his chair as though stung; coffee shot from his cup like a missile and splattered across his lap, across the floor, across the papers on the desk, across my lovingly shined black shoes. For, before I had quite pronounced the name of that immense theological humorist, my lungs seemed to have erupted in a single, tremendous, high-pitched, belching great guffaw, just as if a bewildered donkey had burst into the room. I covered my mouth. I was mortified. I began to apologise, leaning forwards in my seat and scrambling to remove the coffee-sodden papers from the mahogany desk.

Then I heard it again, that terrible sound, that startled guffaw. And before I knew what was happening, I had blurted out the name at last, bellowed it, all in capital letters – "CHESTERTON!" – not so much a name as an air raid siren. And it was only then that I knew it was really too late: I would never get the job, would never hold a position at Harvard Divinity School, would never fulfill my dream of becoming Administrative Assistant to the Dean. For just as Satan fell from heaven, so I had plummeted from my chair on to that luxuriant coffee-stained carpet, and was rolling about the floor in the shrieking grip of a helpless, hilarious, humiliating theological hysteria.

I'm especially impressed by the way he bursts into peals of laughter when he hears the name "Chesterton": the word tends to have the same effect on me.

In fact, I once missed out on an important job opportunity simply because the interviewer – the dean of Harvard Divinity School – happened to mention the name of G. K. Chesterton. We sat in the autumnal light of the dean's office, facing one another across a polished mahogany desk beneath the shadow of towering bookshelves and the high baroque majesty of that Ivy League ceiling. "... And that's the real problem with someone like G. K. Chesterton," he said.

I cleared my throat. I shifted in my seat. I felt my nose twitch as I stifled a little giggle. I concentrated all my mental powers on suppressing the shaking that had started somewhere deep in my diaphragm. I wiped a solitary tear from my eye. I breathed.

At last after a few moments I had calmed myself. I coughed politely into my hand, and opened my mouth to make an erudite remark about Catholic thought on distributist economics – when, to my horror, the dean leaned back in his chair, coffee cup in hand, and said the dreadful word again: "Chesterton." All my defences collapsed. It was as though a gigantic hand had seized me by the rib cage and given me a fierce shake. I covered my mouth. I heard a terrific snort. I wiped my eyes and said, "I'm terribly sorry, I do beg your pardon. We were speaking, I believe, of Ches – Ches – Chester –"

And then it happened. The Dean of the Divinity School leapt from his chair as though stung; coffee shot from his cup like a missile and splattered across his lap, across the floor, across the papers on the desk, across my lovingly shined black shoes. For, before I had quite pronounced the name of that immense theological humorist, my lungs seemed to have erupted in a single, tremendous, high-pitched, belching great guffaw, just as if a bewildered donkey had burst into the room. I covered my mouth. I was mortified. I began to apologise, leaning forwards in my seat and scrambling to remove the coffee-sodden papers from the mahogany desk.

Then I heard it again, that terrible sound, that startled guffaw. And before I knew what was happening, I had blurted out the name at last, bellowed it, all in capital letters – "CHESTERTON!" – not so much a name as an air raid siren. And it was only then that I knew it was really too late: I would never get the job, would never hold a position at Harvard Divinity School, would never fulfill my dream of becoming Administrative Assistant to the Dean. For just as Satan fell from heaven, so I had plummeted from my chair on to that luxuriant coffee-stained carpet, and was rolling about the floor in the shrieking grip of a helpless, hilarious, humiliating theological hysteria.

Saturday, May 7, 2011

Goyang Dikit

ketika rumah kemalingan saat di tinggal suami..

di rumah yang baru kemalingan , seorang suami bertanya kepada istrinya :

suami : mah , ada apa ini ?

istri : rumah kita kemalingan pah

dengan kondisi panik , suami melihat ruang keluarga .

suami : apa?!!! TV kita mana ? dicuri ?

istri : iya pah

suami : terus mamah diem juga?

istri : iya pah

terpogoh pogoh dia masuk ke ruang kerjanya..

suami : laptop dan komputer papah mana mah ? dicuri juga ?

istri : iya pah

suami : terus mamah diem juga?

istri : iya pah

setelah paniknya reda , sang suami melihat kondisi rambut istri yang kusut...

suami : terus mamah di perkosa?

istri : iya pah

suami : terus mamah diem lagi?!!

istri : engga pah , goyang dikit

di rumah yang baru kemalingan , seorang suami bertanya kepada istrinya :

suami : mah , ada apa ini ?

istri : rumah kita kemalingan pah

dengan kondisi panik , suami melihat ruang keluarga .

suami : apa?!!! TV kita mana ? dicuri ?

istri : iya pah

suami : terus mamah diem juga?

istri : iya pah

terpogoh pogoh dia masuk ke ruang kerjanya..

suami : laptop dan komputer papah mana mah ? dicuri juga ?

istri : iya pah

suami : terus mamah diem juga?

istri : iya pah

setelah paniknya reda , sang suami melihat kondisi rambut istri yang kusut...

suami : terus mamah di perkosa?

istri : iya pah

suami : terus mamah diem lagi?!!

istri : engga pah , goyang dikit

Friday, May 6, 2011

Menyelamatkan 1200 Nyawa

Catatan Harian Seorang Wanita yang Menyelamatkan nyawa 1200 Penumpang Kapal Mewah dari Bahaya Tenggelam.

Seorang wanita cantik tengah menikmati perjalanannya dalam kapal pesiar. Dia sangat mengagumi kemewahan kapal itu. Baru pertama kali ia melihat kapal seperti itu. Untuk mengenang perjalanannya, dia menulis dalam buku hariannya.

Tanggal 13:

Bukan hari yang sial… namun keberuntungan buatku. Aku bisa. mengenal kapten kapal dan dugaanku benar… Dia sangat gagah dan tampan… Aahh benar2 beruntungnya aku.

Tanggal 14:

Tanpa kuduga, sang kapten mengajakku makan malam dan… alamak dia juga sempat memuji. kecantikanku… Aku jadi tersanjung.

Tanggal 15:

Dia mengajakku makan malam lagi. Sang kapten ternyata nakal juga… dia mulai berani mengajakku bercinta dan menunggu jawabanku besok.

Tanggal 16:

Dia menagih janji… dengan jual mahal kutolak dia (emangnya gue cewek apaan..) eh…, dia malah mengancam akan menenggelamkan kapal beserta 1200 penumpangnya.

Tanggal 17:

Pagi yang cerah… aku bangga bisa menyelamatkan nyawa 1200 penumpang…

Seorang wanita cantik tengah menikmati perjalanannya dalam kapal pesiar. Dia sangat mengagumi kemewahan kapal itu. Baru pertama kali ia melihat kapal seperti itu. Untuk mengenang perjalanannya, dia menulis dalam buku hariannya.

Tanggal 13:

Bukan hari yang sial… namun keberuntungan buatku. Aku bisa. mengenal kapten kapal dan dugaanku benar… Dia sangat gagah dan tampan… Aahh benar2 beruntungnya aku.

Tanggal 14:

Tanpa kuduga, sang kapten mengajakku makan malam dan… alamak dia juga sempat memuji. kecantikanku… Aku jadi tersanjung.

Tanggal 15:

Dia mengajakku makan malam lagi. Sang kapten ternyata nakal juga… dia mulai berani mengajakku bercinta dan menunggu jawabanku besok.

Tanggal 16:

Dia menagih janji… dengan jual mahal kutolak dia (emangnya gue cewek apaan..) eh…, dia malah mengancam akan menenggelamkan kapal beserta 1200 penumpangnya.

Tanggal 17:

Pagi yang cerah… aku bangga bisa menyelamatkan nyawa 1200 penumpang…

Audio lecture: lessons from Augustine's De Trinitate

Over the past several weeks, my class on the trinity has been working through Augustine's De Trinitate – an immense challenge! Today we reached the great finale of Book 15. So I tried to sum up Augustine's theology of the trinity in a final lecture, outlining a series of brief "lessons from Augustine". I had to record the lecture for some of the students, so I thought I'd also post it here. If you're interested, you can listen below – there are six short parts, each about 10 minutes:

Over the past several weeks, my class on the trinity has been working through Augustine's De Trinitate – an immense challenge! Today we reached the great finale of Book 15. So I tried to sum up Augustine's theology of the trinity in a final lecture, outlining a series of brief "lessons from Augustine". I had to record the lecture for some of the students, so I thought I'd also post it here. If you're interested, you can listen below – there are six short parts, each about 10 minutes: Augustine part 1

Augustine part 2

Augustine part 3

Augustine part 4

Augustine part 5

Augustine part 6

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Most countries roof protects primarily against rain with stylistic factors

A Roof is the covering on the uppermost part of a building. A roof protects the building and its contents from the effects of weather. Structures that require roofs range from a letter box to a cathedral or stadium, dwellings being the most numerous.

In most countries a roof protects primarily against rain. Depending upon the nature of the building, the roof may also protect against heat,

Jacob Taubes: apocalyptic time and the retreat from history

At this year's AAR panel on Jacob Taubes and Christian Theology, I'll be giving a paper titled "Jacob Taubes: Apocalyptic Time and the Retreat from History". I wrote a paper last year on Taubes' interpretation of Paul; this one will focus more on his recently translated works, Occidental Eschatology and From Cult to Culture. Here's my rather long and rambling abstract:

At this year's AAR panel on Jacob Taubes and Christian Theology, I'll be giving a paper titled "Jacob Taubes: Apocalyptic Time and the Retreat from History". I wrote a paper last year on Taubes' interpretation of Paul; this one will focus more on his recently translated works, Occidental Eschatology and From Cult to Culture. Here's my rather long and rambling abstract:In his famous theses on history, Walter Benjamin proposed that only a messianic conception of time can burst apart the claustrophobic historicism of modern thought, with its endless cycle of cause and effect. Jacob Taubes’ work was developed against the same backdrop of modern doctrines of homogeneous time; like Benjamin, Taubes wanted to inject the possibility of freedom into the tragic continuum of history.

Taubes sees Nietzsche and Freud as the two great architects of a modern tradition of ‘tragic humanism’, where human actors are utterly imprisoned by fate. ‘There is no hope for redemption from the powers of necessity.’ Taubes largely accepts this post-Christian tragic vision, especially as a corrective to secularised eschatologies of progress. Yet he also advocates a return to the theological conception of time in Jewish and Christian apocalypticism. If time is endless repetition, then the urgency of political commitment is diffused; we are compelled into a situation of ‘decision’ only where the present stands under the shadow of the end. Politics, Taubes thinks, becomes possible only where time is rushing towards this end, and thus where the present is not trapped in a web of repetition, but is a moment of absolute crisis and ‘distress’.

This accounts for Taubes’ lifelong preoccupation with Gnosticism. For him, Gnosticism is a form of non-revolutionary apocalypticism: its doctrine of time locates us within a moment of urgency and decision, while withholding from us any claim to political power, as though we could bring about the end through our own agency. Early Christian apocalypticism is fertile because it yields up not simply a rival politics, but a rival to politics, ‘a critique of the principle of power itself’.

In Taubes’ thought, therefore, a tragic vision of history is set within a wider apocalyptic context – though not in a way that is directly liberating, or that issues in any specific political involvement. Taubes wants to retain the tragic pessimism of Nietzsche and Freud even while relativising it apocalyptically, just as Benjamin relativises historicism not by arguing for the possibility of revolution but by an immense deferral of historical hope, in which history is broken open by the coming messiah.

In this paper I will explore this unresolved tension – so characteristic of modern Jewish thought – between tragedy and expectation, freedom and fate. I will argue that Taubes’ nostalgia for Gnosticism represents an attempt to relieve this tension; but that Gnosticism, with its retreat into an ‘interior apocalypse’, ultimately fails to break the deadlock of modern historicism. Instead I argue that the realism of early Jewish and Christian apocalypticism – a doctrine not about the interior life, but about history – is the only genuine alternative to the tragic fatalism of modern thought.

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

Kena Tilang Polisi

Pada awal pembicaraan ketika seorang pria ditilang oleh pak polisi :

"Apa salah saya Pak? Saya pake helm, pake jaket, punya SIM, STNK bawa, kenapa saya di tilang ?"

Polisi menjawab " “Sebel aja gw liat lo… muter2 pake jaket dan pake helm tapi nggak pake motor."

"Apa salah saya Pak? Saya pake helm, pake jaket, punya SIM, STNK bawa, kenapa saya di tilang ?"

Polisi menjawab " “Sebel aja gw liat lo… muter2 pake jaket dan pake helm tapi nggak pake motor."

Monday, May 2, 2011

Berhenti Merokok

Arto: apa kamu sudah menghentikan kebiasaan merokokmu itu ?

Ito : sudah 2 bulan saya tidak merokok

Arto: baguslah kalo begitu, tapi asap yang ada dikamar mu ini ?

Ito : oh tenang aja sob, ini bukan asap rokok, tapi cerutu.

Ito : sudah 2 bulan saya tidak merokok

Arto: baguslah kalo begitu, tapi asap yang ada dikamar mu ini ?

Ito : oh tenang aja sob, ini bukan asap rokok, tapi cerutu.

Sunday, May 1, 2011

Menjadi Dokter

Apa cita-citamu setelah dewasa cu ?" Tanya kakek pada cucunya

"Jadi dokter kek !" Jawab cucunya dengan ringan

"Kalau begitu kakek bisa berobat gratis dong" kata kakek dengan senang

"Tapi kek itu tidak mungkin" Kata cucu dengan enteng

"Loh memangnya kenapa??" sahut kakek

"Sebab saat saya sudah menjadi dokter, pasti Kakek sudah ALMARHUM" sambung cucunya lagi.

"Jadi dokter kek !" Jawab cucunya dengan ringan

"Kalau begitu kakek bisa berobat gratis dong" kata kakek dengan senang

"Tapi kek itu tidak mungkin" Kata cucu dengan enteng

"Loh memangnya kenapa??" sahut kakek

"Sebab saat saya sudah menjadi dokter, pasti Kakek sudah ALMARHUM" sambung cucunya lagi.

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Systematic theology job: Geneva

In his Confessions, Augustine asks the beautiful, aching question: "Do we remember happiness as one who has seen Carthage remembers it?" I have never been to Carthage: but I have been to Lake Geneva.

I mentioned the other day that theologian, historian, and grand amateur de jazz Christophe Chalamet will soon be leaving Fordham for Geneva. Christophe also informs me of a job opening at the University of Geneva's Faculty of Protestant Theology. The position involves working on a doctoral dissertation in systematic theology, as well as working as a theological assistant (e-learning, research support, administration, etc).

The position is nearly full-time (80%), and pays around 50,000 Swiss francs per annum (about 38,000 euros). Applicants must have excellent French-English, a Masters degree or equivalent, and a strong interest in 20th-century and contemporary theology. Further details are available here.

I mentioned the other day that theologian, historian, and grand amateur de jazz Christophe Chalamet will soon be leaving Fordham for Geneva. Christophe also informs me of a job opening at the University of Geneva's Faculty of Protestant Theology. The position involves working on a doctoral dissertation in systematic theology, as well as working as a theological assistant (e-learning, research support, administration, etc).

The position is nearly full-time (80%), and pays around 50,000 Swiss francs per annum (about 38,000 euros). Applicants must have excellent French-English, a Masters degree or equivalent, and a strong interest in 20th-century and contemporary theology. Further details are available here.

Monday, April 25, 2011

Off the Shelf: six types of reading

Last time, there were various comments about reading habits. So in this video I provide a typology of six types of reading.

Books mentioned in this video:

And since I've mentioned Chesterton's book on Aquinas, here's a delightful account of how the book was written – this is an excerpt from Dale Ahlquist, G. K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense (Ignatius Press 2000), chapter 9:

When G. K. Chesterton was commissioned to write a book about St. Thomas Aquinas, even his strongest supporters and greatest admirers were a little worried. But they would have been a lot more worried if they had known how he actually wrote the book.

When G. K. Chesterton was commissioned to write a book about St. Thomas Aquinas, even his strongest supporters and greatest admirers were a little worried. But they would have been a lot more worried if they had known how he actually wrote the book.

Chesterton had already written acclaimed studies of Robert Browning, William Blake, Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson, Chaucer, and St. Francis of Assisi. Nonetheless, there was a great deal of anxiety even among Chesterton's admirers when in 1933 he agreed to take on the Angelic Doctor of the Church, the author of the Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Aquinas.

Without consulting any texts whatsoever, Chesterton rapidly dictated about half the book to his secretary, Dorothy Collons. Then he suddenly said to her, “I want you to go to London and get me some books.”

“What books?” asked Dorothy.

“I don't know”, said G. K.

So Dorothy did some research and brought back a stack of books on St. Thomas. G. K. flipped through a couple of books in the stack, took a walk in his garden, and then, without ever referring to the books again, proceeded to dictate the rest of his book to Dorothy.

Many years later, when Evelyn Waugh heard this story, he quipped that Chesterton never even read the Summa Theologica, but merely ran his fingers across the binding and absorbed everything in it.

[...] And what kind of book did he write? Étienne Gilson, probably the most highly respected scholar of St. Thomas in the twentieth century, a man who devoted his whole life to studying St. Thomas, had this to say about Chesterton's book: “I consider it as being without possible comparison the best book ever written on St. Thomas.”

Books mentioned in this video:

- Steven Millhauser, The Knife Thrower: And Other Stories (Vintage 1999)

- G. K. Chesterton, St Thomas Aquinas [1933], in The Collected Works of G. K. Chesterton, Volume 2: The Everlasting Man, St. Francis of Assisi, St Thomas Aquinas (Ignatius Press 1987)

- Michael Jensen, Martyrdom and Identity: The Self on Trial (T&T Clark 2010)

- Augustine, Confessions, trans. Henry Chadwick (Oxford UP 1992)

- Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans, trans. Edwyn C. Hoskyns (Oxford UP 1933)

- G. W. Bowersock, Peter Brown, and Oleg Grabar, eds., Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World (Belknap 1999)

- Augustine Day by Day: Minute Meditations for Every Day Taken from the Writings of Saint Augustine (Catholic Book Publishing 1999)

- James Alison, Knowing Jesus (2nd ed; SPCK 1998)

And since I've mentioned Chesterton's book on Aquinas, here's a delightful account of how the book was written – this is an excerpt from Dale Ahlquist, G. K. Chesterton: The Apostle of Common Sense (Ignatius Press 2000), chapter 9:

When G. K. Chesterton was commissioned to write a book about St. Thomas Aquinas, even his strongest supporters and greatest admirers were a little worried. But they would have been a lot more worried if they had known how he actually wrote the book.

When G. K. Chesterton was commissioned to write a book about St. Thomas Aquinas, even his strongest supporters and greatest admirers were a little worried. But they would have been a lot more worried if they had known how he actually wrote the book.Chesterton had already written acclaimed studies of Robert Browning, William Blake, Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson, Chaucer, and St. Francis of Assisi. Nonetheless, there was a great deal of anxiety even among Chesterton's admirers when in 1933 he agreed to take on the Angelic Doctor of the Church, the author of the Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Aquinas.

Without consulting any texts whatsoever, Chesterton rapidly dictated about half the book to his secretary, Dorothy Collons. Then he suddenly said to her, “I want you to go to London and get me some books.”

“What books?” asked Dorothy.

“I don't know”, said G. K.

So Dorothy did some research and brought back a stack of books on St. Thomas. G. K. flipped through a couple of books in the stack, took a walk in his garden, and then, without ever referring to the books again, proceeded to dictate the rest of his book to Dorothy.

Many years later, when Evelyn Waugh heard this story, he quipped that Chesterton never even read the Summa Theologica, but merely ran his fingers across the binding and absorbed everything in it.

[...] And what kind of book did he write? Étienne Gilson, probably the most highly respected scholar of St. Thomas in the twentieth century, a man who devoted his whole life to studying St. Thomas, had this to say about Chesterton's book: “I consider it as being without possible comparison the best book ever written on St. Thomas.”

Menerobos Rambu Lalu Lintas

Setelah lama ikut Bapaknya jadi sopir metromini, maka sang anak pun sekarang sudah dianggap bisa dan akhirnya bawa metromini sendiri.

Di sebuah rambu lalu lintas dari kejauhan lampu menyala kuning. Sang anak malah menginjak gas dan menerobos lampu merah.

Penumpang: (marah) goblok lu mau cari mati ya!!!

Dijawab sama sopirnya: tenang aja saya sudah diajarin bapak saya, yang penting selamat.

Nah di rambu yang selanjutnya pun demikian. Walau lampu merah tetap diterobos. Nah di rambu ke 5 lampu nyala hijau. Tetapi tiba-tiba rem diinjak mendadak. Penumpang heran dan tanya kenapa lampu hijau berhenti.

Jawabnya: saya takut bapak saya jalan dari arah lain. !!!!!!!!!

Di sebuah rambu lalu lintas dari kejauhan lampu menyala kuning. Sang anak malah menginjak gas dan menerobos lampu merah.

Penumpang: (marah) goblok lu mau cari mati ya!!!

Dijawab sama sopirnya: tenang aja saya sudah diajarin bapak saya, yang penting selamat.

Nah di rambu yang selanjutnya pun demikian. Walau lampu merah tetap diterobos. Nah di rambu ke 5 lampu nyala hijau. Tetapi tiba-tiba rem diinjak mendadak. Penumpang heran dan tanya kenapa lampu hijau berhenti.

Jawabnya: saya takut bapak saya jalan dari arah lain. !!!!!!!!!

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Rowan Williams: a letter to a six-year-old

Speaking of Rowan Williams, I was quite touched by a news story in The Telegraph.

Speaking of Rowan Williams, I was quite touched by a news story in The Telegraph.A six-year-old Scottish girl named Lulu wrote a letter to God: “To God, How did you get invented?” Lulu's father, who is not a believer, sent her letter to various church leaders: the Scottish Episcopal Church (no reply), the Presbyterians (no reply), and the Scottish Catholics (who sent a theologically complex reply). He also sent it to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who sent the following letter in reply:

Dear Lulu,Now that's what I call real theology! Isn't this exactly why we need theological specialists: not to make the faith more complicated and obscure, but to help us grasp how simple it really is?

Your dad has sent on your letter and asked if I have any answers. It’s a difficult one! But I think God might reply a bit like this –

‘Dear Lulu – Nobody invented me – but lots of people discovered me and were quite surprised. They discovered me when they looked round at the world and thought it was really beautiful or really mysterious and wondered where it came from. They discovered me when they were very very quiet on their own and felt a sort of peace and love they hadn’t expected. Then they invented ideas about me – some of them sensible and some of them not very sensible. From time to time I sent them some hints – specially in the life of Jesus – to help them get closer to what I’m really like. But there was nothing and nobody around before me to invent me. Rather like somebody who writes a story in a book, I started making up the story of the world and eventually invented human beings like you who could ask me awkward questions!’

And then he’d send you lots of love and sign off. I know he doesn’t usually write letters, so I have to do the best I can on his behalf. Lots of love from me too.

+Archbishop Rowan

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)